The Dimensions of a Cave by Greg Jackson. Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 480 pages. 2023

Greg Jackson’s The Dimensions of a Cave, one of the more accomplished American novels of the twenty-first century, begins in imagery that lends substance to a recurring form:

The island clung to the mainland by a spit of sandbar as low and shingled as a manicured walk and could not therefore be properly called an island. Still we called it that, “the island,” and at times, when the ocean cycles and planets aligned, the perigean king tide with its liquid cargo brought the water up over the lip of that persistent littoral, briefly severing all tie to the shore and bringing the fact of the land into sympathy with its name.

The exquisite picture establishes the novel’s frame—newsmen convened at a rickety beach house to hear an old friend’s wild tale—while breathing life into its theme, the physics of truth itself, made tangible through the sensuous music of Jackson’s prose: a “perigean king tide” heaved over a “spit of sandbar” to bring a referent “into sympathy” with a word. Within The Dimensions of a Cave, truth is a mercury that tides with the sympathy and antipathy of all things, squeezed into beads by convergence or left in quivering pools by disjunction. Unfalteringly lyrical, philosophically attentive, the novel seeks these truths as if scanning anamorphic images stretched between the dipoles of experience: “chaos” and “pattern,” “objective” and “subjective,” “inner and outer,” “maps” and “territory,” “cognition” and “primal syntax,” “dreams” and “waking life,” “life and death,” the self and other “freestanding souls.” Neither the metaphysician’s ephemeral quarry nor the propagandist’s spun clay, truth is the very stuff of our communal reality.

In a novel fundamentally concerned with the world beyond the self, aesthetic commitment redounds to a moral sensibility.

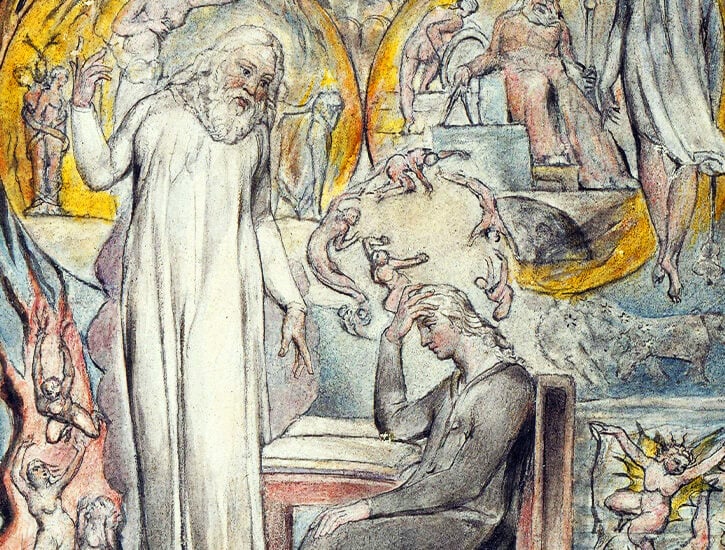

What defines this reality, and why should we live there? These are the novel’s questions, inherited, as its title implies, from Plato’s canonical ‘Allegory of the Cave,’ which describes fettered prisoners who confuse reality for the shadows cast against a cave’s low wall—“like the screen in front of people that is provided by puppeteers,” as it’s described in C.D.C. Reeve’s translation of Republic. The Dimensions of a Cave has little trouble recovering the allegory in a defamiliarized United States, where investigative reporter Quentin Jones divulges the story for which his friends have gathered, recollections of chasing the figments of power into a virtual universe, the cave of his own mind, everted by a covert technology that gives life “the character, and the insignificance, of a dream.”

Jackson’s first book, Prodigals (2016), was a collection of vivid short stories largely about young Americans becoming aware of the narcissism abetted by their innocence. Besides his acuity, erudition and humor, Jackson’s most impressive capability is for description (a careless turn through Prodigals yields cactuses appearing to rich kids on a bender “to glow, as round and chartreuse as tennis balls, the air wholesome with a hovering feculence, the play of shadows on the far slopes giving them the cast of spalted wood”). This method—neglected or passé, depending on which literary gargoyle you consult—distinguished Jackson from contemporary writers unwilling or unable to dedicate themselves to such lapidary standards, resigned to forfeit description of the world to the unrivaled fidelity of video. The prose of Jackson’s first novel is its own achievement, for both the allure and consistency of its sentences, which lull the reader into a gauze, overwarm and murmured, flush with the coral glow of eyelids awaiting those in an afternoon’s amniotic doze. With atmospheric meditations worthy of DeLillo and astonishing comparisons (the eyes of a man “ease down . . . like the belly of a jet landing in the distance”; leaves flutter in the wind like “the settling cymbal of distant surf”) The Dimensions of a Cave offers an unimpeachable defense of language’s capacity to freight an environment with feeling, mentality, and the grammar of theme. In a novel fundamentally concerned with the world beyond the self, this aesthetic commitment redounds to a moral sensibility. Jackson’s style, diction and vision are his own, but his novel is one of few to credibly resume the affirmative literature envisioned by David Foster Wallace (a literature unembarrassed by its principles), which, until now, had seemed most powerfully realized in Wallace’s aborted masterwork, The Pale King.

Whereas Wallace examined the IRS agent, a profession responsible for the enforcement of our civic contract, Jackson raises the journalist, that streetwise philosopher, charged with the stewardship of a “single, knowable reality” that is “every last person’s right to know.” Of the four men gathered at the “island,” none are as devoted to this code as Quentin, who eschewed the editorial perches of broadsheet publishing in the nation’s “capital” to remain an investigative reporter, a lowly gnat navigating the intersecting corridors of bureaucracy and industry with sardonic wit and disobedience. A middle-aged daydreamer, childless, party to a fraying romance, Quentin foils himself against hacks who think “press releases offered useful context,” and by his grimy idealism avoids the piety of journalists (fictive and actual) eager to lionize themselves in the virtue of a thankless trade.

Don’t get me wrong, Jackson does not deny his reader the thrills of clandestine mystery or the weary musings of a sleuth (“We may have seen ourselves as the descendants of noir detectives”) who never clocks out and returns to a dusky apartment, as Quentin does, to banter with the cat. Though The Dimensions of a Cave is generously plotted (how could it not be?), it coasts toward the surprise that awaits its protagonist, the type of world-shuffling realization signaled by a dolly zoom. Quentin’s narrative holds to journalism’s weathered standbys (i.e., follow the money, question authority, doubt yourself) and is often clarified through the institutional cynicism of its lingo. Admittedly “not immune to the beckonings of paranoia,” he stops to consider “the state of play” and speaks of “dirty money,” “trial balloons,” and “gunmetal éminences.”

Quentin is tipped off by a conscientious analyst to a revived “defense research” program called VIRTUE (“Very immersive real-time user environments”). Described by Quentin as “high-tech gaslighting,” the technology exploits advances in neural interfaces and computational power to sustain manipulable illusions indistinguishable from waking life—a tool that doesn’t exactly demand imagination from the American intelligence apparatus, which intends to use it to bloodlessly extract information from agents on the wrong side of the War on Terror, or some fictionalized version of it. Quentin’s whistleblower is disturbed by the technology’s limitless potential for abuse but also by a basic misgiving: “Could we say with confidence that cutting a person off from reality was not torture every bit as severe as the physical sort?” The government ultimately intervenes on Quentin’s report by convincing his publisher to print a “bowdlerized” version, buried “under the fold” next to a “goat-choker on education reform.” Enjoined from further investigation, Quentin continues following the breadcrumbs to discover a long-lost protégé, Bruce Willrich, at the center of the ordeal.

Bruce joined Quentin years ago as a cub reporter at a municipal paper after penning a “six-thousand-word exposé” on payday loans for his student outfit. Quick to rancor, ashamed of his father’s wealth, Bruce’s idealism was fanatical, genuine but compensatory. During an unspecified bout of U.S. adventurism in the Middle East, Quentin counseled Bruce to become a war correspondent. Bruce, soon disgusted with what counted for reportage in the green zone, chose to embed with a high-contact unit until he fell off the grid. Years passed and Bruce was presumed dead. When a remorseful Quentin learns Bruce is marooned in virtual reality, not dead but stubbornly dreaming, he submits to a dubious group so that he can venture into the cave after his pupil.

As Quentin interviews the scientists, bureaucrats, and power brokers responsible for the virtual world he eventually enters, his narrative assumes the character of a philosophic “pilgrimage,” as his listeners finally regard it. Quentin must relinquish facile distinctions between the real and virtual, between the touchable grass of meatspace and the counterfeit pixels of the metaverse. For he learns that the technologies underlying VIRTUE bootstrap on the “brain’s heuristic method” for synthesizing a coherent tableau from limited information—a simulation we name “reality.” “Such a notion challenged the reporter’s credo,” Quentin reflects, “which proposed a unitary reality for the knowing and taking. And if we could accept that some part of reality existed out there and some part inside us, would we ever agree on where one stopped and the other began?”

Even if we could, Quentin comes to appreciate, the set of truths on which our minds converged would never be the immutable foundation we yearn to discover. Our quest for reality is restricted to a thin valency between the mind and world, where thought rebounds against the curve of “pure form,” the protean folds of dreams and insanity, and runs against the standing waves of “chaos,” as Jackson terms it, a noumenal realm for which Blake’s “every thing possible to be believ’d is an image of truth” serves as signpost. A computer scientist informs Quentin that “vision, and cognition broadly, breaks a sensory input of ever-changing chaos into a subset of recurrent and comprehensible forms.” Later, a deconstructionist reminiscent of Derrida or Lacan describes his ambition to probe “the transparent, ineffable medium of our lives,” though he remains unsure whether “it is better not to know, better to remain in the embrace of comprehensible illusion, than to aspire to see the chaos of the truth.”

In Plato’s allegory, prisoners emerging from the dim cave are “dazzled” by the glare of a wider reality, a temporary blindness that nonetheless illustrates the paradox of absolute truth. As we approach it, we hear the voice of a god, stare directly into the sun, and so frustrate or destroy the very senses we use to grasp those phenomena. The Quixotic mind fares no better in attempting to peer beyond the glare into a “mind-independent” reality. Still, Quentin, at times, senses the glimmers and reflections of this unbearable blaze. “How unequipped we are,” he remarks, for “the glare that lives in the raw outdoors,” the “unqualified weight of life’s mystery: its rawness without any padding of ideas,” the “slumbering behemoth” that is the “outside world . . . so placid and plodding and immense,” the “glare of reality unmediated by such sweet and sorry lies.”

What cannot be perceived or known may yet be experienced. Jackson anchors Quentin’s consciousness around frequent ruminations (captivating in their own right) that are commonly interrupted by direct experience, reminding us that there exists another channel to transcendent reality besides thought. It flutters against the nerve endings, unfolds through the course of time that Quentin habitually departs. The miracle of our bare existence: that we are here, alive, aware, now, in a world of contingent forms and provisional verities cast against the formlessness of oblivion—a truth that is unavailable to skepticism because it is inaccessible to thought. It was this same presence that Wallace set out to uncover and revere within The Pale King, the treasure at the bottom of consciousness, “right here before us all, hidden by virtue of its size.”

That Jackson so often rouses his characters to this inexhaustible reality through touch—the tender reminder of another’s existence—accentuates its communal function. Soothed into sleep by “a low golden sun and hum of a car,” Quentin stirs to discover a woman’s “hand lay on my forearm.” Exhausted by a crowd, Quentin recognizes his not-quite-estranged lover beside him, finding that “she had taken my arm . . . in a companionship that needs no words.” Once in the dreamworld, Quentin assumes the waker’s role, placing “the back of my hand” against the cool cheek of a woman absorbed in thought, or touching Bruce’s face after he delivers a misanthropic screed. “[Bruce] appeared shocked, even childlike, for a brief moment—as if I had touched his lips to mine.”

This definition of reality is Jackson’s final offering: a luminous cytosol through which we contact each other, a medium whose realness is validated by our communion. The epistemic maintenance of journalism, science, and scholarship remains necessary but tantamount to a greater imperative to locate one another on stable ground. Illusion, then, begins in departure from our shared understanding, in retreat to private worlds tailored from alternative facts, deviant theories, and competing narratives. These “virtual” realities, merely enhanced by simulative technology, recommend themselves to centers of power, who see divided minds as territory easily conquered. The Dimensions of a Cave follows the suit of commercial art about virtual reality (e.g., the Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy, Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, Christopher Nolan’s Inception) by depicting it as an instrument of deception, control. By the end of the novel, however, these apprehensions seem little more than apologia for the moral hazards of self-deception. Returned to the daylit world, Quentin learns that the technology of VIRTUE has been appropriated to create “the first truly postmodern video game,” an “immersive sim . . . designed for VR headsets” that constructs a “simulation drawn from our memories and fantasies.” Don’t we already know the honest seductions of simulated reality, the promise to lift our worldly impingements and negate the reality of other people? No deceit or coercion is needed to satisfy the ancient wish for what Jackson calls the “loneliness of a god.” We’ll wait in line for it.

The minotaur of The Dimensions of a Cave is found in the labyrinth of the common mind, which arranges society to service its solipsism. Above all, Jackson implicates our faculty of abstraction in detaching the mind from a shared reality. There is no greater simulator than the human brain, which represents the world within itself, models reality by abstracting and manipulating the elements it perceives through the senses. Of course, this capacity underlies almost every advancement of human civilization. But abstraction works precisely by shutting itself out from the chaos of direct experience and so always risks confusing its schematic of the world for the world itself. The peril that Jackson identifies is usefully clarified in The Master and His Emissary by literary-critic-turned-psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, who argues that the bilateral hemispheres of the brain enable two profound modes of engagement with the world. Whereas the right hemisphere attends to direct experience, its left counterpart, “the hemisphere of abstraction,” attends only to “the virtual world that it has created . . . making it powerful, but ultimately only able to operate on, and to know, itself.”

Bruce, who, at points, seems to channel McGilchrist, believes “our abstractions ruled us and turned deadly precisely for what made them powerful in the first place: that they suggested we could encounter and subdue far more than we could.” The error registers against the novel’s background, the War on Terror, which Bruce experienced firsthand as a confutation of the high-concept delusions that motivated it: that it was possible to wage war against a global tendency; that a superpower could remake foreign countries in its own idealized image; that a government could prevent any and all atrocities from befalling its citizens. Such harebrained ambitions would seem like strokes of genius in the sterile war rooms of abstraction, where map is substituted for territory, scheme confused for execution, and bodies dissociated into numbers.

Upon finding Bruce in the dreamworld, Quentin learns that his friend has darkened his theories in the intervening years. By removing us from the medium we share with others, abstraction inevitably erodes the intuitive sense that we stand apart from other lives as unmistakably real as our own. What Bruce once termed “the abstraction of other people” is the necessary condition of human violence. Bruce treats Quentin to a relentless yet mesmerizing litany of bloodshed (Good God does the callow idealist reap his due!) over thirty pages of historical evidence selected from across culture and epoch. The Aztecs’ ritual sacrifices. The Roman bloodsports. The inventive terrors of Chinggis Khan. Marquis de Sade’s sexual torture. The Western slave trades. The British starvation of India and Ireland. The meat-grinder of the Somme. Pancho Villa’s banditry. Lothar von Trotha’s extermination of the Herero. The Nanjing massacre. The Holodomor. The ethnic vengeance campaigns of Rwanda. Bruce concludes this barbarous cavalcade, fittingly, with the Nazis, who are distinguished for their employment of “judicious rationality” and “bureaucratic efficiency” in a system of butchery prosecuted by “largely bourgeois professionals, physicians, architects, and lawyers” to the order of millions dead. But we cannot access the magnitude of terror and agony represented by what Bruce terms the “abstract arm of numbers,” upon which “human devastation seems immaterial and dreamlike.” The inescapable dominion of abstraction signals the victory of the self that wields it to foreclose imaginative access to the inner lives of other people, and to the suffering we cause them.

Illusion begins in departure from our shared understanding, in retreat to private worlds tailored from alternative facts, deviant theories, and competing narratives.

So we come to Jackson’s amendment to the standard interpretation of the allegory. Plato’s cave typically is presented to undergraduates as a convenient fable for the value of education and the responsibilities it bestows upon those who receive (and pay tuition for) it. The philosopher prefigures the student by ascending into the greater lights of reality and feeling obliged to return and enlighten his befuddled peers. Jackson would remind us how these “dispassionate ideals . . . loop back around into the passions by an alternate circuit, the proud wiring of our self-regard.” The actual “warning of the cave” must concern the self that orients between the antipodes of illusion and reality, between “a childish desire for the infinite” and “love,” which is “the belief that other people are real.” It must be this love that compels one to return to the cave and rouse his fellows, or motivates a writer to spend years laboring at such an enlightening novel. But the outcome of any enlightenment depends first on its method of disillusionment—a lesson Socrates learned the hard way. The Dimensions of a Cave concludes largely in an essay of self-interpretation that interrupts the berceuse of concepts and language that sustained the novel’s own painless dream. But it was through this sudden extraction that I realized how deeply I had dreamed, how far I had drifted into Jackson’s laminations, away from the common miseries of waking life—so much that I didn’t notice how seldom Jackson depicted human suffering, how far he had advanced an affirmative novel without confronting the spiritual sickness it is tasked with overcoming, the self-inflicted miseries that predominated Wallace’s fiction. Is my insistence to see suffering reflected in art, so Bruce-like in its dourness, a holdout from my maturity? Probably. But the art that would dispel this illusion would show how all fantasies justify themselves through the very suffering they perpetuate. It is the lie that sustains our every solipsistic and hedonic illusion, whether it emanates from a screen or assembles in the recess of lonely mind: that the truth is unbearable; that our pain originates in daylit reality instead of being the needless cost of living among the shadows.

Source: thebaffler.com