This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Efforts to crack down on TikTok are picking up momentum in Congress. What was once a Trump-led effort boosted by Republicans has since become a bipartisan priority for lawmakers hoping to look tough on China in an election year.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic:

New Momentum

Efforts to ban TikTok in the United States—or at least to attempt to force the Chinese-founded company ByteDance to divest TikTok—have recently picked up momentum. What once seemed like a quixotic, Trumpian endeavor has now shaped into a congressional bill that a bipartisan House committee voted unanimously to advance last week. The bill’s pointed provisions, which will most likely be brought to a broader House vote this week, refer to TikTok by name and would force other large apps owned by foreign adversaries to sell to a domestic owner or else be shut down.

Lawmakers’ motives for taking on the app boil down to a fear that TikTok could feed data on American users to the Chinese government, and that the platform could be used to spread misinformation and censor American users. (The company denies the validity of both concerns, referencing “Project Texas,” its initiative to store Americans’ user data and review its algorithmic recommendations through the American-run company Oracle.) President Joe Biden said last week that he would support the bill if it passed through the Senate, which has not yet introduced companion legislation.

In spite of its bipartisan backing in the House, the bill still faces a blend of legal, logistical, and political barriers. Any legislation that might curtail free speech will be under tight legal scrutiny. Previous efforts to ban the app—including a Trump-era executive order and a state law in Montana—quickly ran into First Amendment challenges. “There is a very high bar to restrict speech in the United States,” Caitlin Chin-Rothmann, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me in an email. “The U.S. government would need to prove that a TikTok ban is narrowly tailored to advance a significant government interest, and that there are no less restrictive means of advancing that interest.” The current bill frames its intention as a forced sale rather than an outright ban—a move that aims in part “to circumvent those types of legal challenges,” according to Kate Ruane, the director of the Free Expression Project at the Center for Democracy and Technology, which opposes the House bill.

How a sale of TikTok would actually work is unclear. The bill gives TikTok roughly six months to find a new American owner, but landing a buyer might prove tough—and a sale may not go over well in China. Few American companies could afford to spend billions on such a purchase. And the large tech companies that could swing it might not be interested in such a massive purchase—or willing to take on the legal risk. Any acquisition from a competitor would likely face antitrust challenges. A spokesperson for TikTok said that it sees this congressional move as effectively a ban.

Young people, as you may have heard, love TikTok, and banning the app in an election year seems like an easy way to invoke their ire. (Donald Trump, after zealous efforts to take down the app while president, recently pivoted in his views, saying yesterday that young people would “go crazy” without TikTok.) But the bipartisan consensus so far in the House “inoculates members from electoral retribution” from annoyed TikTok users who can’t pin the blame on one party, Sarah Kreps, a Cornell University professor and the director of its Tech Policy Institute, told me in an email. Still, the whole episode hasn’t done much to assuage concerns that politicians don’t understand the importance of social media and internet culture. “Some TikTok users have bemoaned that Congress still believes that TikTok is comprised of ‘young people dancing videos,’ rather than as a space for legitimate cultural and political expression,” Robyn Caplan, an assistant professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, told me in an email.

If the bill ends up passing, its provisions would set a clear domestic precedent: Other foreign-run platforms could be subject to similar actions. Ruane is concerned about what such a ban would mean abroad too. Already, American-owned digital platforms have been blocked in other countries, including China, and a TikTok ban could give authoritarian regimes the license to ban others for “pretextual” reasons. The potential fallout, she told me, could further limit users’ access to information and freedom of expression across the world.

Because many voters are cold on China, Kreps said that backing anti-China legislation could help lawmakers politically. But banning TikTok outright, Ruane argued, would not actually solve the core issue of the Chinese government being able to access American user data through other means online. In her view, a better way to safeguard those data would be to create comprehensive consumer-privacy laws that would require apps including TikTok, as well as American companies such as Facebook, to face more restrictions on how they handle user data. That kind of comprehensive approach, although perhaps less politically punchy than the House bill, may well improve life on the internet beyond TikTok too.

Related:

Today’s News

- The Biden administration announced a new $300 million military-aid package for Ukraine.

- During a House Judiciary Committee hearing, Special Counsel Robert Hur defended his report’s recommendation to not charge President Biden for mishandling classified documents and stood by his characterization of the president’s memory issues. A transcript of Hur’s hours-long interview with Biden was also released.

- Haitian Prime Minister Ariel Henry announced that he will resign after weeks of gang violence plunged the country into a state of emergency.

Evening Read

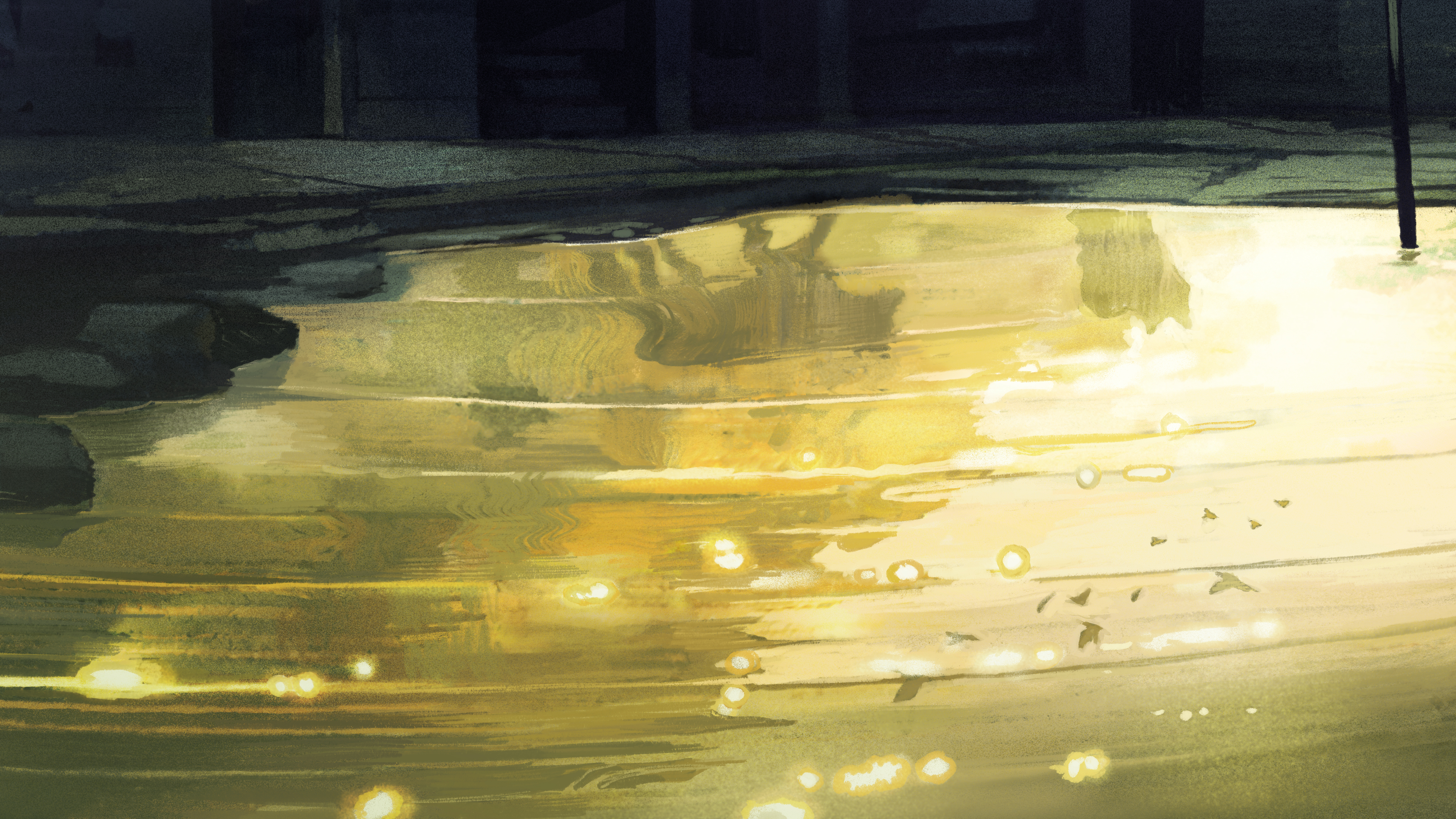

Did We Fall in Love With the Wrong House?

By Emily Raboteau

I can’t talk about our house in the Bronx without telling you first about the pond out front. Given how much worse flooding can be elsewhere in New York City—even just two blocks to the east along the valley of Broadway, where the sewer is always at capacity—not to mention elsewhere in the world, I’m embarrassed to gripe about my personal pond. These days, such bodies of water are everywhere. Mine is not the only pond, but merely the pond I can’t avoid …

I ruminate over the pond. It has caused me not just embarrassment but shame. It has turned me scientific, made me into a water witch. I understand that the pond is beyond the scope of any one person, or any one agency, to handle, and that it’s perilous to ignore. The pond is a dark mirror; in it, our house appears upside down, distorted. It reflects deeper problems of stewardship and governance and the position of our house in relation to both. We are privileged to own a home. Yet we live on land that will drown, that is inundated already.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. Why does romance feel like work nowadays? These two books dissect the crisis of modern love.

Watch. Love Lies Bleeding, a new film starring Kristen Stewart, is a relentless crime thriller grounded by a winning love story.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Source: theatlantic.com