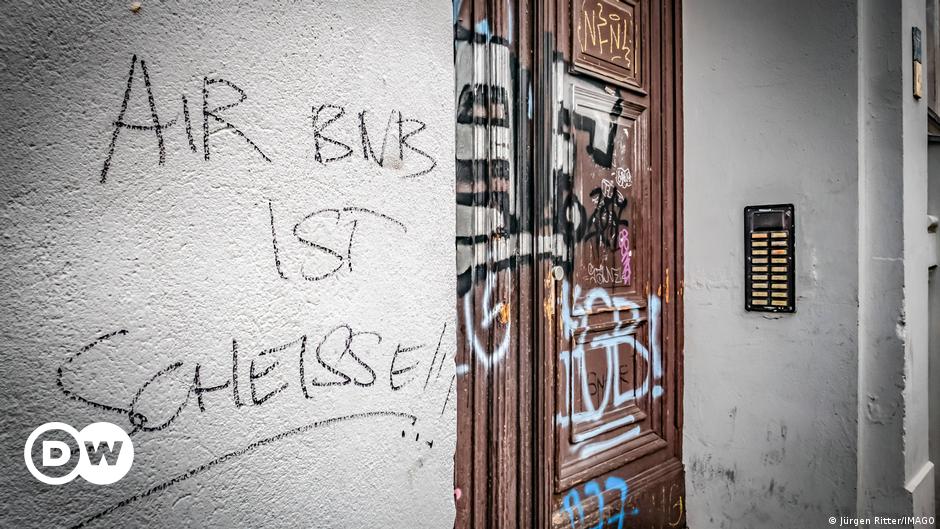

Berlin‘s local authorities and renters’ rights groups are hoping that a recent court ruling will free up thousands of holiday apartments for the rental market, in a city where rents have shot up in the last two years.

In what the Mitte district authority called a “pioneering” judgment, the Berlin higher administrative court ruled last month that the city could force owners to put holiday apartments on the rental market even before the city’s “misappropriation” law banning them went into effect in 2014.

Sebastian Bartels, managing director of the Berlin Tenants‘ Association (BMV), described the court verdict as “very important.” He estimates that up to 10,000 apartments could be brought back onto the rental market across the whole of Berlin.

Airbnb and Berlin: A long legal battle

February’s decision marked the culmination of an eight-year legal battle over a building in central Berlin where 27 regular apartments had been turned into 37 furnished holiday apartments. The smallest of these are currently being rented out for around €200 ($220) a night, while the penthouses cost €3,000 – €4,000 ($3,300 – $4,300) for three nights.

The owner of the block took the local district to court for refusing to grant the property protection on the grounds that the old law still applied. The case made it all the way to the German Federal Constitutional Court, which sent it back to the Berlin court, which upheld its earlier verdict to side with the district.

The German capital’s “prohibition of misappropriation law” of 2014, bans owners of residential properties from leaving apartments empty or renting them out as holiday apartments on a daily or weekly basis. Exceptions can be made, for example for subletting part of an apartment, but require a permit.

Up until now, the law had only been enforced on properties that had been turned into holiday apartments after the law came into effect, but the new ruling clarifies that it can also apply to holiday apartments that already existed before 2014.

New tools

Mitte’s district Mayor Stefanie Remlinger welcomed the verdict in a statement: “With this ruling, the court has given us as a district the tools to tackle one of the most pressing social problems in our city: the lack of housing.” She said the city

was now “in a position to combat the illegal letting of apartments … and to reclaim urgently needed living space for regular letting.”

The ruling could potentially have a major effect. Remlinger told the RBB broadcaster that her authority is planning to re-examine some 1,700 properties with multiple apartments, two-thirds of which she thinks could be forced to put living space back on the rental market. That stock is desperately needed in the city, with rents in Berlin spiking in the last two years: According to property market research organization empirica-regio, the average Berlin rent was stable throughout the COVID pandemic at around €10 per square meter but rose to over €14 by the last quarter of 2023.

“Thousands of cases from before the implementation of the misappropriation law could not be processed — nearly ten years’ worth,” Bartels told DW. “Most of the holiday apartments are in the attractive areas of central Berlin, and they are a huge factor in driving inhabitants out.”

Sebastian Bartels of the Berlin Tenants’ Association pointed out that property owners had been engaged in what he called “deadline surfing” — extending the legal battle as long as possible by coasting from one appeal to the next, and so exploiting the often tortuous pace of the court system. “It all took too long, and in the meantime this misappropriation has been going on and on,” said Bartels. “And that means we’ve lost thousands of apartments over the last ten years. That’s bitter.”

But the exact numbers are not clear, partly because there is no centralized register of all the empty properties in the city, which local authorities would need to be able to count how much living space Berlin had at its disposal.

“We just don’t have the data – we don’t know how many apartments are lost to Airbnb or other providers. It’s ridiculous that we don’t have such a register in such a big city, where 83% of inhabitants are renters,” he said. “There are no efforts from the city administration to establish such a register.”

European Union: A new obligation for Airbnb

Airbnb did not offer a comment on the specific court ruling, but pointed to previous statements in which it said that landlords who offer apartments on its platform were obliged to register as part of its “initiative for responsible tourism and housing protection.” The platform also said that 40% of its Berlin users used Airbnb to share their private homes to bolster their incomes.

But that wasn’t good enough for the European Union, which has recently passed a new framework for short-term rentals that requires platforms like Airbnb to not only register properties, but also check compliance to local rules, and put data on a central database for local authorities. For Barbara Steenbergen, member of the executive committee at the International Union of Tenants, this is a major victory.

As she put it, the problem up until now has been that while most major cities in Europe have laws to prevent “misappropriation,” they often fail to enforce them because authorities simply don’t know where the apartments are, who the landlords are, and whether the holiday apartments are complying with the relevant rental period or space restrictions.

“This was the case in all the big cities, from Amsterdam to Zagreb,” Steenbergen told DW. “The cities asked the Commission to make a framework that obliges the platforms to disclose: Where are the apartments? How long are they rented out for? On which basis? What was the rental income?” Now, only if all these factors are in line with local rules do landlords get a short-term rental registration number that allows them to use Airbnb.

“It means a lot less burden for cities,” she said. “This is extremely necessary when you see the macroeconomic point-of-view. Currently, we do not build enough new affordable housing — we’ve had a problem with the stop of construction all over Europe. So the cities are now trying to ensure that the existing stock becomes affordable again.”

Edited by Rina Goldenberg

While you’re here: Every Tuesday, DW editors round up what is happening in German politics and society. You can sign up here for the weekly email newsletter Berlin Briefing.

Source: dw.com