Image: Jonathan Glass and Sarah Hyden

Until reasonably accurate and ecologically appropriate language is used by the Forest Service and their collaborators to describe their forest management strategies and activities, fundamental ecological issues will not be well understood, and the necessary paradigm shift to protect our forests and communities will not occur.

A range of misleading language and terms, picked up by many including the media, create confusion and miscommunication. For example, the term “forest restoration,” when used by the agency, often means aggressive cutting and too-frequent burning of large tracts of forest, sometimes removing as much as 90% of standing trees and most of the natural forest understory. Generally conservation organizations and members of the public do not consider such activities, with the resulting damage to soils and waterways, to be ecological restoration. Instead they consider restoration to be strategically improving the overall structure and function of forest ecosystems and processes while causing minimal impacts. Strategies to achieve this include replanting riparian areas, protecting soil microbiomes, promoting beaver habitation, fencing out cows, and decommissioning excessive forest roads. The goal is to create conditions that hold moisture in forest ecosystems, which makes landscapes naturally more fire resistant and bring them into a state of greater ecological integrity.

“Restoration” has become a euphemism the Forest Service uses, borrowed from the language of conservation, that makes what the agency actually does to our forests more palatable. Other misleading agency forest management terms are “thinning” (removing most of the vegetation from a forest is too heavy-handed to be considered thinning), “fuels treatments” (trees and understory are so much more than fuels), “forest health” (there are no clear parameters for forest health), and forest “resiliency.”

“Resiliency” means the capacity of an ecosystem to return to its previous condition after impacts, such as fire. Forests that have been impacted by having had large amounts of vegetation removed due to aggressive cutting and continued too-frequent prescribed fire do not tend to return to their previous condition, and perpetually remain in a degraded state. Untreated or very lightly-treated forests that are allowed to regenerate after a fire may return to their previous condition. So which is resiliency?

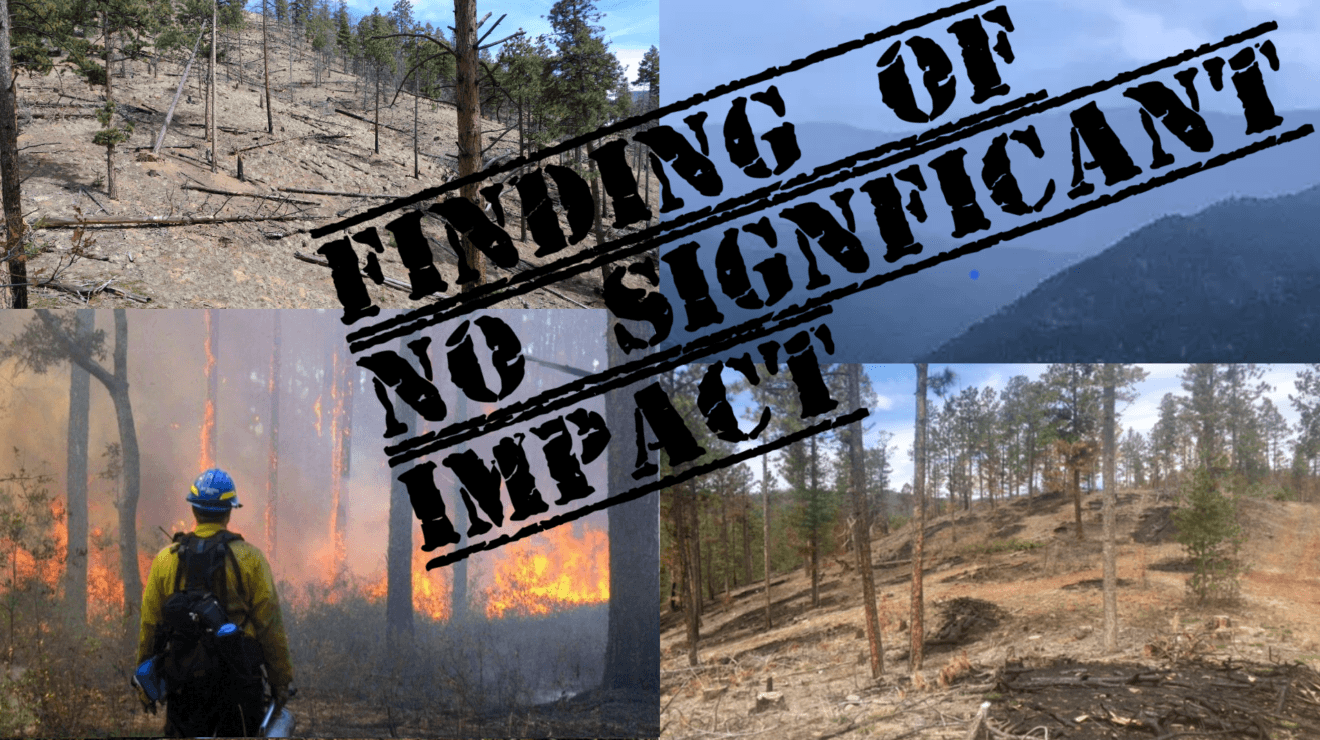

The Forest Service concludes analysis of the vast majority of its vegetation cutting and burning projects with a “Finding of No Significant Impact.” Such findings are based on criteria of significance although the findings are often challenged, but the actual words imply that the impacts are relatively minor and not substantive enough to be particularly concerned about – even though we can often plainly see otherwise. A Finding of No Significant Impact is routinely applied to highly damaging projects that leave forests ecologically broken for decades to come. The impacts of such projects cannot be reasonably called “not significant.”

Interested parties trying to obtain information about Forest Service landscape management often must rely on FOIA, or the Freedom of Information Act. However, substantive FOIA requests can now literally take years. When the requests are finally fulfilled, it’s often too late to be useful. To call this “Freedom of Information” from the Forest Service is yet another misnomer. It might be more accurately called the “Nearly Impossible to Obtain Information Act” at this point.

In 2022, three wildfires were ignited by the Forest Service in the Santa Fe National Forest during implementation of prescribed burns, which escaped and burned a total of 387,000 acres. There have been many articles and op-eds written locally and nationally about these fires that point to them as examples of why we need even more thinning and burning of our forests to moderate the effects of wildfire, without mentioning the fact that the fires were actually caused by escaped prescribed burns — or that fact was included, but as more or less a footnote. The Cerro Grande Fire, which was ignited in 2000 due to an escaped prescribed burn (by the US Park Service that time) has also been used as such an example. To do so, without acknowledging the importance of agency prescribed burns having precipitated these same wildfires, amounts to a kind of circular reasoning that suggests we need even more of what caused much of the wildfire we are trying to prevent – albeit with some procedural changes and further safety measures. It’s a misuse of both language and logic, and clouds the underlying issues.

Articles and op-eds concerning the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire often make statements such as “the Forest Service accidentally triggered New Mexico’s largest wildfire.” This is not entirely false, as the fire was not started on purpose. But what is much more accurate to write is that the Forest Service recklessly or negligently ignited New Mexico’s largest wildfire. The agency had to know it was a substantial risk to ignite the Las Dispensas prescribed burn, which precipitated the Hermits Peak Fire, during a particularly intense high wind pattern, with red flag warnings nearby. The agency had to be clear that if the fire did escape, it would likely spread fast and be very difficult to extinguish until the monsoons came months later. Locals were warning those responsible for the burn not to light up a burn at that time, because it was obvious to them that it would be very dangerous. The Forest Service did not heed their warnings. The Chief’s review of the Hermits Peak Fire indicates that the Forest Service was feeling pressured to catch up on implementing prescribed burns, because they have committed to greatly increasing cutting and burning treatments in our forests, even though safer burn windows are decreasing due to the warming and drying climate.

Additionally, Forest Service personnel knew fire was spreading from the Calf Canyon burn piles 10 days before the Calf Canyon Fire officially broke out during a high wind event. They made efforts to contain the spreading pile burns. They also carried out aerial surveillance over the pile burn area during those days. It was predictable that in early April, the winds could rapidly spread any escaping fire. That the agency did not make a full out effort to address every pile, considering that they knew some of them had been smoldering and that high winds were coming, has at least the appearance of recklessness and/or negligence. Almost two years later, no analysis of this fire has been released by the Forest Service. To use the word “accidentally” in regards to the ignition of this destructive wildfire, which burned entire communities, does not provide any realistic understanding of what likely occurred. A realistic understanding could be a basis for making sure such a catastrophe never happens again.

During the weeks after the Calf Canyon Fire began, the Forest Service identified the cause of the fire as “under investigation,” even though they had been surveilling and attempting to contain the escaping pile burns from the beginning of the incident. Given this, “under investigation” cannot be construed as a reasonably accurate description of what the Forest Service knew about the cause of the Calf Canyon Fire. They surely knew the cause from the very beginning with an extremely high degree of probability. It took several weeks for the Forest Service to finally announce that the Calf Canyon Fire was also precipitated by their own actions. This lack of transparency created even more distrust and anger in an already traumatized community.

In a recent article about the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, the Forest Service was quoted as stating “Record-setting blazes have become common in the West, where risks have reached crisis proportions.” This statement is somewhat true, and yet highly misleading at the same time. It would be substantially more accurate to at least mention that much of the total “wildfire” burning in our forests is intentionally ignited by the agency.

In August of last year, I wrote an article titled “Forest Service Wildfire Management Policy Run Amok.” In it, I described three New Mexico wildfires in just over a year that were greatly expanded due to intentional ignitions by the US Forest Service. I provided evidence, based on thermal hot spot maps, that during the over 325,000 acre Black Fire, New Mexico’s second largest wildfire, up to half of the fire was likely intentionally ignited by the Forest Service.

Since that time, I met with some local Forest Service leadership along with other conservation organization representatives, and a Forest Service fire specialist confirmed that the agency did intentionally ignite much of the Black Fire, from approximately 10 miles to the south and 6 miles to the northwest of the main fire.

Of course, I asked why the Forest Service expanded and ignited the fire to this extent, burning most of the Aldo Leopold Wilderness, and with substantial collateral damage. We were told it was done for “resource management objectives.” That means the fire expansion was essentially a huge Forest Service intentional burn, similar to a prescribed burn, but with no prescription or advanced planning and/or NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) analysis. Yet the Forest Service has continued to call this a “wildfire.” with no mention of the role they played in the expansion of the fire. That is a misleading use of the word “wildfire,” since much of the fire was deliberately ignited by the agency. This perpetuates a cycle of even more cutting and burning, since the Forest Service is trying to moderate the effects of the seemingly increased amounts of wildfire.

So what actually is the wildfire “crisis” that the Forest Service is talking about? I believe it’s possible that overall, the Forest Service ignites or expands wildfires to an extent approaching a third to a half of what is counted as wildfire acres burned. No one should simply accept the Forest Service’s use of the term “wildfire crisis” when the agency is expanding and igniting such a major proportion of the fire on our landscapes. Such wildfire expansions have become policy — it’s referred to as applied wildfire. If we are experiencing a wildfire crisis, then it’s a crisis that can be quickly mitigated by the Forest Service simply refraining from igniting so much unplanned wildfire in our forests.

Fires of all intensities are natural and beneficial to fire-adapted forested landscapes. An open and honest process that defines clear parameters for managing wildfire is required in order to safely and effectively allow moderate amounts of naturally-ignited wildfire to burn in our forests. A revised wildfire management policy must be created through a transparent NEPA process. This means using language that is not loaded with unproven and controversial assumptions or agendas. Otherwise, what has happened to the residents so severely impacted by the Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, and to our forests, many of which have become over-cut and over-burned, will happen again and again. We should not accept the agency’s statements about a wildfire crisis uncritically.

As long as the media, conservation organizations, and the public continue to accept euphemisms and double-speak to describe forest management strategies and activities, we will not collectively have the understanding to resolve the underlying issues. The issues must be publicly acknowledged with clear and direct language, even though there will always be substantial differences of opinion. The Forest Service and their collaborators should be thoroughly questioned on their use of misleading language. Somehow, the Forest Service and their collaborators, along with conservation organizations, conservation scientists, and the public, will have to come together with a mutual ecological language and understanding. Then, we can design ecologically beneficial projects that allow our forests to reset in a warming climate.

Image composite photos:

Top left – Santa Fe watershed, thinned in the early 1990’s and burned twice. Photo: Fred King.

Top right – Prescribed burn smoke over the Santa Fe ski basin. Photo: Satya Kirsch.

Bottom left – A USFWS firefighter watches a prescribed fire. Retweeted by Santa Fe National Forest. Photo by USFWS.

Bottom right – La Cueva Fuel Break, thinned in 2017 and burned once. Photo: Lyra Barron.

Source: counterpunch.org