Stressed out? Get chewing: can a wellness rebrand make Americans buy gum again?

The stuff has been around, in some form, for millennia. But with sales in a long decline, marketers are taking things full circle

When was the last time you saw someone chewing gum? 1998, maybe? 2007? Chances are, it probably wasn’t recently. Like high heels and affordable housing, chewing gum appears to be going extinct.

Gum’s popularity has been declining globally for a while now thanks to increased competition from products like breath mints and mobile phones distracting us from impulse purchases while shopping. The pandemic, however, drastically accelerated gum’s decline: sales dropped by nearly a third in the US in 2020, according to the market research firm Circana. No prizes for guessing why: you don’t need minty fresh breath for Zoom calls.

Even after people emerged from lockdown, sales didn’t recover. Gum sales worldwide in 2023 were 10% below 2018 figures, according to Euromonitor. In the US, the drop has been particularly pronounced: last year 1.2bn units of gum were sold in the US, 32% fewer than in 2018. Sales in dollars, however, are at pre-pandemic levels. That’s largely because chewing gum – like everything else – costs more than it used to just a few years ago.

Gum’s fading fortunes may be panicking its manufacturers, but it’s not all bad news. There is an argument to be made that we should ban it like Singapore did in 1992. Chewing gum, after all, may freshen up your breath but it has littered our cities. Almost 90% of England’s streets are stained with gum, according to research by Keep Britain Tidy. In the US, during one gum cleanup operation in New York, “some 20,000 wads were scraped from one spot on Times Square alone”.

Peeling gum off the streets costs a fortune. It’s hard to find accurate statistics, but councils in Britain spend £60m each year cleaning an estimated 2m pieces of gum from pavements, according to figures from 2018. It has been estimated that each stick of gum costs an average of 3 pence (about 4¢ in US dollars) to produce and 10 pence (13¢) to be scraped off the ground.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. Chewing gum, in various forms, is one of the oldest habits there is. Stone age teenagers were chewing birch bark tar in Scandinavia 10,000 years ago, possibly for pleasure, medicinal purposes, or to use as a glue. Gum also has a long history in the Americas. “We know that cultures like the Aztec and the Maya were chewing things like chicle [a tree resin],” notes Jennifer Mathews, professor of anthropology at Trinity University and the author of a history of chewing gum. Certain Indigenous cultures also chewed spruce resin, and European settlers picked up (ie stole) the habit. Then, in 1848, the first commercial chewing gum went on sale in the US.

It may be diminutive in size but gum has always been loaded with cultural meaning and the subject of various moral panics. Mathews notes that the Aztecs frowned on chewing gum in public: “It was very sexualized and known as a marker for sex workers.” And that association continued well into the 20th century. “Often in stereotypes in movies or in television, it’s the bad kids who are chewing gum, right? On the set of the movie Grease, they’re rumoured to have got through 100,000 pieces of gum on set – the T-Birds and the Pink Ladies were gum-chewers because that was a marker of the bad kids.”

Gum has also been viewed as a habit of the lower class. “Emily Post, the great etiquette guru, didn’t even mention gum in the first several editions of her etiquette books, because she just thought, well, no decent person is even going to consider chewing gum,” Mathews notes. “And then it became so popular that she was finally forced to address it and basically say it was like watching a cow chew its cud.”

Carole Middleton, Kate’s mother, caused an uproar in the UK when she chewed gum at Prince William’s Sandhurst graduation ceremony in 2006. The episode was seized upon as an example of why William was never going to marry from common stock like the Middletons. (Spoiler alert: he did.)

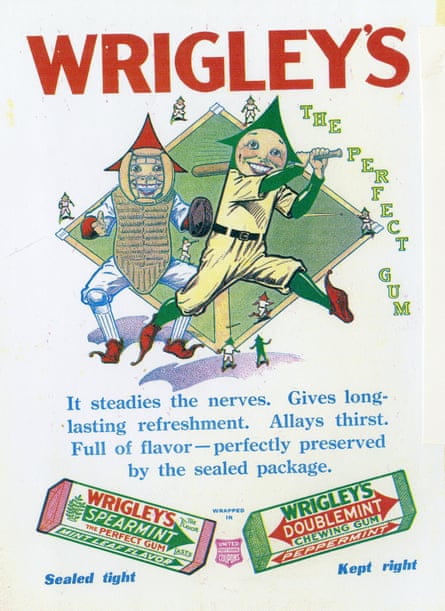

Despite the fact that there’s always been a certain amount of social stigma attached to gum, it has – until relatively recently – been a wildly successful product. That’s thanks to William Wrigley Jr, who started selling gum in the 1890s and was a marketing and advertising genius. Wrigley always managed to find a way to make gum relevant and insert it into consumer culture. During the 1910s, for example, Wrigley advertising was focused on the idea that chewing gum was a health aid that would help digestion and a tag line urged people to “chew it after every meal”.

Another recurring theme in Wrigley’s advertising was that gum chewing would relieve stress. A 1931 campaign claimed “biochemical research has now proved that chewing gum is a definite help in smoothing out tense and tired nerves”. As well as relieving stress, gum was also positioned as a beauty aid. “A graceful cheek line …depends very much upon chewing,” another print ad from the 1930s proclaimed.

Wrigley’s biggest coup, however, was probably convincing the US military to include chewing gum in its rations. Wrigley argued that it was the perfect thing for a soldier because it reduced stress, staved off hunger and quenched thirst. The military then helped spread the chewing gum habit around the world and “legitimized the habit”, says Daniel Robinson, professor of information and media studies at Western University.

“There’s really nothing that can go wrong with something like the Wrigley … brand,” Warren Buffett said when he teamed up with Mars to buy the chewing manufacturer in 2008. “It’s literally true that they’ve faced the test of time over decades and decades and decades and people use more and more of their products every day.”

Mars is doing its best to sell us on the sticky stuff again. This year the Wrigley brand’s owner came out with an ad campaign it hopes will revive gum’s fortunes by positioning it as an almost instant stress reliever.

Alyona Fedorchenko, vice-president for global gum and mints in Mars’ snacking division, told the Associated Press that, in the summer of 2020, she spoke to a nurse in a hospital Covid-19 ward who chewed gum to calm herself. “That, for us, was the big ‘aha!’” Fedorchenko said. The multimillion-dollar campaign shows people in stressful situations and urges people to use gum “quiet your mindmouth”. (Which isn’t complete nonsense, to be fair; there are studies which show chewing can help with both focus and stress.) Mars has said that the brand refresh is the “most significant change to its chewing gum brands in 100 years”.

Rather than being a drastic departure for gum, however, this focus on stress relief and wellness feels like gum has gone full circle and we’re back to Wrigley’s early health claims. An ad from 1916, for example, urges people to reach for gum when “work drags”, because it will “steady your stomach and nerves”. Which is basically the olde time equivalent of saying “quiet your mindmouth”.

Linking gum with wellness worked in the 1910s, but is it going to work now? Alex Hayes at the food consultancy Harris and Hayes is cautiously optimistic. “The global wellness market is estimated to be worth more than $1.5tn, so it’s no surprise that Mars wants a piece of the pie,” Hayes says. “We’ve seen the success of categories such as tea repositioning their products via functional claims and messaging – teas for good sleep, mental clarity, stress relief, etc. So it comes as no surprise that Mars is risking the same approach.”

However, Harris notes, customers are increasingly worried about processed foods and are eager to move away from artificial ingredients. The jury’s out on just how effective repositioning chewable plastic as a health supplement is going to be. Consumers might find the idea hard to swallow.

Source: theguardian.com