A stunning photo archive reveals a time before the walls and checkpoints, when Palestine was not defined by its ailments but by its industries and cultures

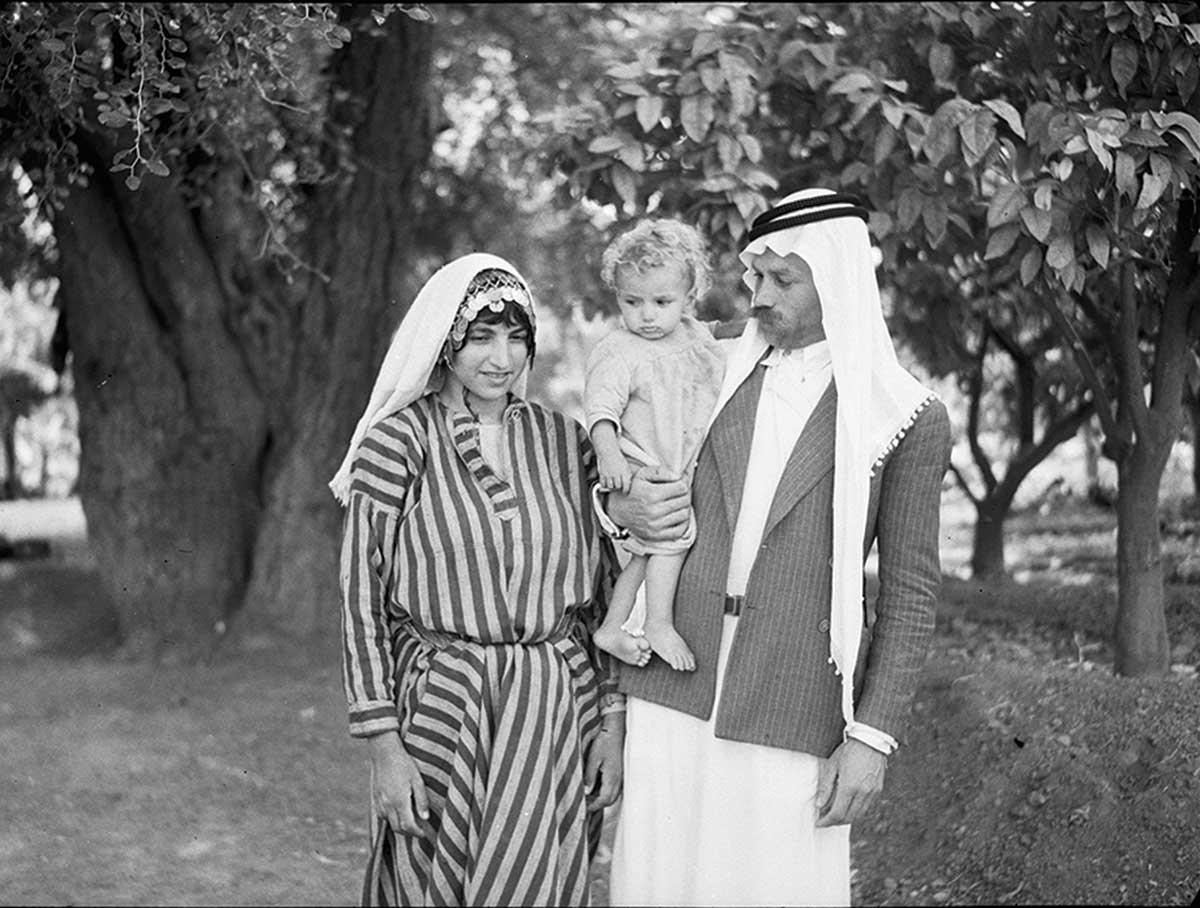

Three generations from the village of Dhahiriyya (located between Hebron

and Beersheba), February 9, 1940.

I am writing this introduction in English and Arabic, and it is in these moments that the profound chasm between these two languages reveals itself. In English, there is a need to riddle the page with facts and figures detailing the essential cruelties of an atrocity that should be—and should have long been—internationally recognized. I’m tempted to squeeze into these lines a history lesson, to list the names of the various terrorist paramilitaries that formed the Israeli military that’s terrorizing us today; the number of massacres, exiles, refugees; the endless hectares of stolen land; the pregnant bellies split open in Deir Yassin. There is no need for such contextualization in Arabic: The Nakba breathes down our necks, invading our national identity and contorting our earliest encounters with our sense of self. It is relentless. It happens in the present tense, everywhere on the map. For some households, it began when a grandfather was dispossessed in Jaffa and sought refuge in Gaza, where it continues in the rumble of the warplanes across the blockaded enclave, introducing his grandchildren to their first—or perhaps third, or sixth—war. Not a corner of our geography is spared, not a generation.

And it is seemingly ubiquitous, following us even in exile. A Palestinian born in Lebanon’s Ein El-Hilweh refugee camp, and not in their grandparents’ Akka—which is both far and near, less than 100 kilometers away—will live tortured by their aborted potential, deprived of citizenship and freedom of movement. And it is absurd: Settlers with New York accents, armed with rifles, can escape criminal charges in the United States to squat in a Jerusalemite’s home, backed by their army, judiciary, and God (their favorite real estate agent).

Still, most, if not all, of this well-documented theft and bloodshed is denied and obfuscated by prominent political, media, and academic institutions in the Anglophone world.

Before conjuring the ability to write a few coherent paragraphs prefacing these photos, all I could think while flipping through them was: What have they done to you? What have they done to Palestine? I was struck by the images of Palestine before the walls and the colonies and the checkpoints clogged its arteries; images captured between towns and villages, now separated by concrete barriers and worlds apart, that were once intertwined socially and economically. Our eyes seldom encounter Palestine before the Israeli regime, a Palestine defined not by its ailments but by its industries and cultures. Yet it is important to resist the urge to romanticize that era. One must situate these photographs within the proper socioeconomic context and ask about what is not represented in these images: Who had access to cameras? Who was behind those cameras? What can be said of those who lived far from the flashbulbs and tape recorders? Where do we look for their fossilized legacies? The tessella of beautiful, unseen photographs that forms as you turn these pages is as illuminating as it is incomplete. There are many conversations we should be having with our grandparents, at their dinner tables, before their deathbeds, and even more work to do if we are to ensure that the victims and resisters of the present-day Nakba aren’t merely acknowledged in fleeting headlines.

These photos, along with the many others that appear in Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine Before the Nakba, which was published in February, reaffirm that Palestine’s history does not begin in fleeing. Not only do they defy the brutal revisionism on the part of the empires and mercenaries seeking to vanquish us; they also disrupt the engineered cultural and political mystification of the Nakba that has, for generations, made its undoing seem impossibly remote.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read. It takes a dedicated team to publish timely, deeply researched pieces like this one. For over 150 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and democracy. Today, in a time of media austerity, articles like the one you just read are vital ways to speak truth to power and cover issues that are often overlooked by the mainstream media.

This month, we are calling on those who value us to support our Spring Fundraising Campaign and make the work we do possible. The Nation is not beholden to advertisers or corporate owners—we answer only to you, our readers.

Can you help us reach our $20,000 goal this month? Donate today to ensure we can continue to publish journalism on the most important issues of the day, from climate change and abortion access to the Supreme Court and the peace movement. The Nation can help you make sense of this moment, and much more.

Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Source: thenation.com