New York Governor Kathy Hochul unfurled a subway “safety” plan last week. It included assigning 750 National Guard and 250 state police and Metropolitan Transit Authority officers to the subway—in addition to the 1,000 NYPD officers the mayor added in February—to check riders’ bags. The governor insisted that her plan is designed to protect New Yorkers and keep them riding the trains.“My No. 1 priority is the safety of all New Yorkers,” she said. “Downstate,” she said, “does not function without a healthy subway system that people have confidence in—I have to do this for them.”

As a lifelong subway rider here in “downstate,” I can tell from her plan that the governor has only a limited understanding of what we need in the way of “a healthy subway system.” I immigrated to the city in 1994 at age 7, and have been taking the subway—largely on my own from the very beginning—in the three decades since. I rode through the late 1990s, when the transit system saw an all-time high in recorded crimes; into 2020, when ridership dropped; and through 2021, when anti-Asian attacks rose. The governor’s plan does dedicate $20 million for 10 teams of mental-health workers, which could be beneficial (assuming those teams really do get vulnerable New Yorkers much-needed resources). But the rest of the plan does not seem to contemplate how the subway system works in practice. How do bag checks prevent people from carrying weapons in their pockets or under their clothes? How does one efficiently administer fair checks in a system that sees 3 million riders a day, and countless congested stations during rush hour? How can law-enforcement omnipresence in high-traffic stations in high-income areas offer anything to far-flung, low-traffic stations, which score worst on safety and harassment?

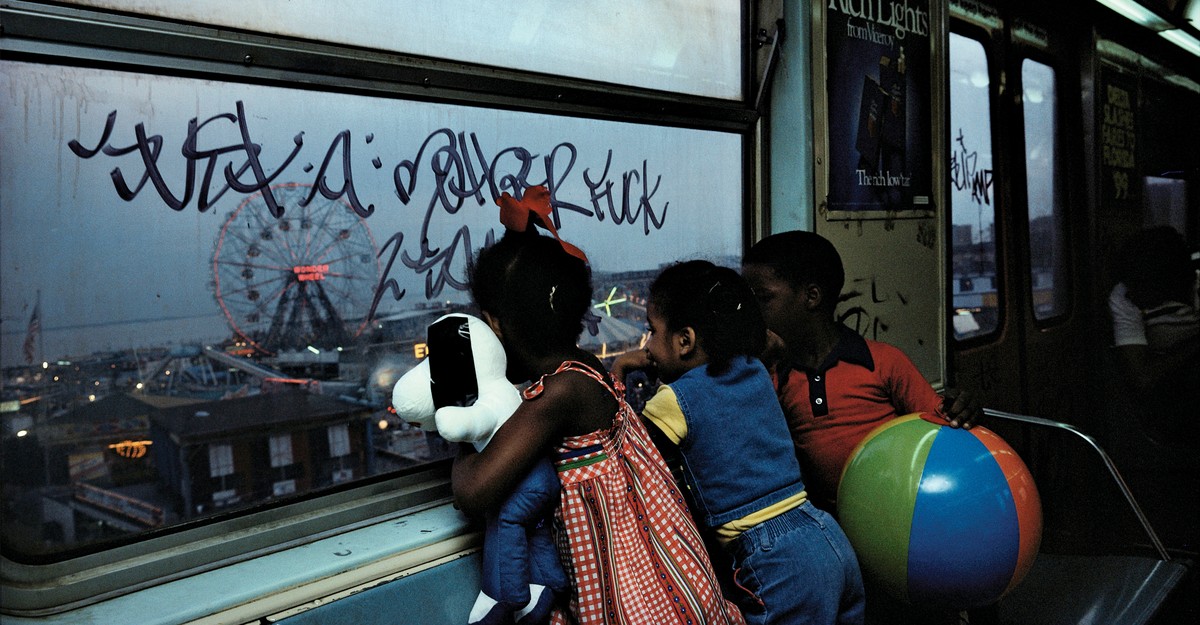

And the plan misapprehends what makes riders feel safe: not cops or soldiers, but fellow riders. Ask any New Yorker what they love about the subway—and what makes them feel safest down in those busy tunnels—and they will say the community of their fellow riders. The kindness of the brisk good Samaritans who stop just long enough to carry luggage up the stairs without a word; the infectious energy of dancers who bring showtime to cars and platforms across the city; the laughter exchanged after sharing a very New York moment of dodging a subway rat. Nowhere on this list is the presence of national militia and state law enforcement—no, that is a burden, not a perk; we ride the subway in spite of, not because of, such features.

As for the purported lack of safety, it’s unclear whether that is real. Mayor Eric Adams said on social media the very same day the governor announced her new plan that transit crime last month was down 15 percent compared with the same month last year (murder, shootings, and car thefts are also down). He declared that “the safest big city in America just got even safer.” The governor’s intervention in our city’s lifeblood is perhaps an unsurprising political move in an important election year. But at what cost? Every car and platform holds New Yorkers who could benefit from not more policing but more public services—that is, more funding for the public libraries,for which the budget was slashed so greatly that all Sunday hours were eliminated, and for which the mayor just this week proposed further cuts that would also eliminate Saturday hours; foremergency mental-health-personnel training programs, the budget for one of which was recently reduced by $12 million; and indeed, for the subway itself, a public good that belongs to all New Yorkers regardless of race, income, or status, and that faces its own budgetary threats.

In 2020, when white-collar New Yorkers had the privilege of abstaining from the subway, their poorer, more marginalized counterparts continued to take the train because they had no other choice. These are the very individuals whom the governor’s plan might deter from riding the subway: People of color, for instance, are far more likely to be stopped by law enforcement, to be criminalized and institutionalized. The governor’s plan compounds existing structural barriers to equity and justice.

And then, of course, there are the undocumented New Yorkers, of whom I used to be one. When I was growing up in the ’90s, riding the subway to the public school where I was fed the free lunch that stood between me and starvation, my biggest fear was seeing cops in the subway.

I still remember the first time a cop stepped into my car when I was on the F train, heading from East Broadway to the tenement-style home my parents and I shared with other immigrant families in Brooklyn. I was in a packed rush-hour car; there was scarcely floor space for the shuffle of feet as passengers got on and off. My mother was with me that day, and when I saw the uniformed officer embark, I grabbed her hand without turning to look at her. I listened to the blood rushing in my ears during the long minutes as the train descended lower in the tunnels, under the East River, and then rose again on the other side, where, at York Street, the doors pinged open. The officer stepped out.

It was then that I regained my senses, and realized with a start that my mother was not in fact where I thought she had been. And then, a beat later, I realized that the hand I had been holding was not hers. I still remember looking down at the hand and tracing it up to its wrist, elbow, and shoulder, before finally arriving at the face of its owner: a woman I did not know, whom I’d never seen before and haven’t seen since, but who gave me the warmest smile.

That smile made me feel safe. In a city with limited space for a poor, hungry, undocumented kid, the subway became one of my few havens. The subway kept me fed and educated.The subway is where I first read some of my very favorite library books, teaching myself English one word at a time; it is where I wrote the first draft of my childhood memoir, tracing and healing my deepest wounds; and it is where I first started to understand what home might feel like in America. When I read the news last week, a kaleidoscope of subway memories played in my mind, and I wondered how I might react to the news if I were still undocumented, still living in poverty and fear.

The governor emphasized that she is not forcing anyone to undergo bag checks. Those who refuse to submit to a check can “go home,” she said: “You can say no. But you’re not taking the subway.” Where, I ask, does that leave the countless New Yorkers for whom the subway is the only way home?

Source: theatlantic.com