The funny thing about the concept of cancel culture is that its popularization coincided with the demise of the mechanisms through which a person might truly be exiled from public life. The mainstream is now fractured into pieces; former gatekeepers in the media and entertainment industry are constantly undermined; the internet has created anarchic new routes for public figures to reach an audience. When an entertainer is canceled, it mostly means that certain moneyed interests—such as a publicly traded company that must cater to the diverse sensitivities of investors or consumers—are more hesitant to work with them. But it doesn’t mean that regular people can’t, or won’t, still engage with whoever succeeds at grabbing their attention.

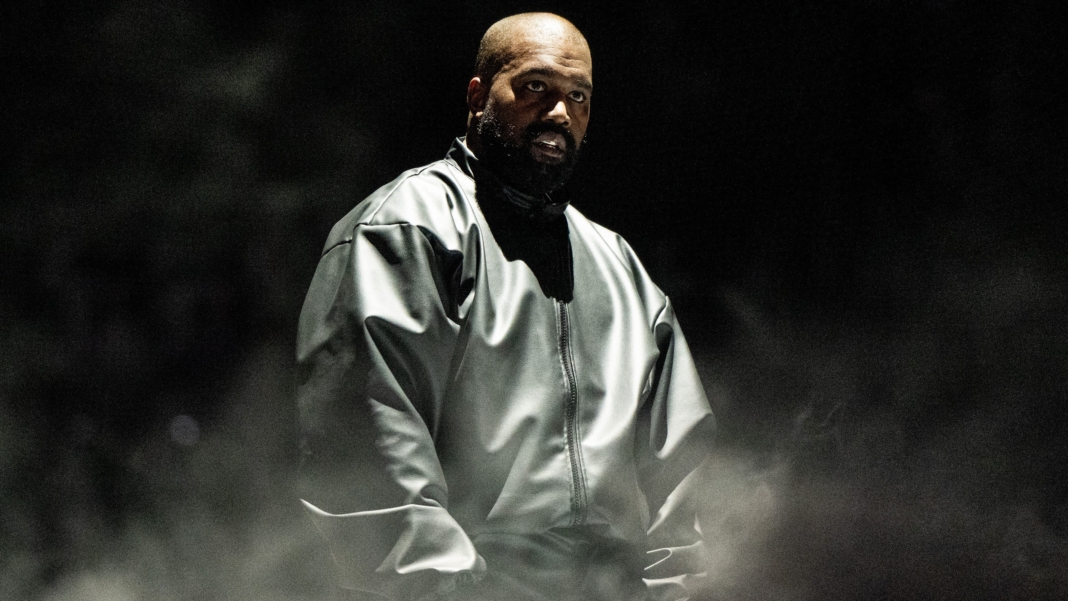

These facts have been proved time and again in popular comebacks for disgraced figures, but the recent success of Ye, formerly Kanye West, is a particularly telling example. Last week, “Carnival,” off his recently released collaborative album with Ty Dolla $ign, became his first No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 since 2011. It’s an eerily apt hit for a cultural climate charged by visions of incipient fascism and war, and a case study in how embattled artists can exploit the power of a good hook.

Never an uncontroversial celebrity, Ye went even further in 2022 by repeatedly praising Hitler during an interview with the conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. Adidas, which allegedly put up with behind-the-scenes bigotry and abuse from Ye for more than a decade, exited a profitable deal with him. Even Elon Musk, who’s hardly known for sensitivity toward the Jews, felt compelled to briefly boot Ye off X (formerly Twitter) after the rapper posted a swastika.

In the run-up to his new album, Vultures 1—by ¥$, his supergroup with Dolla—Ye published an apology in Hebrew, in which he said, “It was not my intention to offend or demean.” His sincerity seemed dubious, given that he’s also recently been photographed wearing the merchandise of a neo-Nazi metal band. Vultures included collaborations with prominent hip-hop figures such as Dolla and Travis Scott, but Ye had trouble clearing samples from Ozzy Osbourne, Nicki Minaj, and the estate of Donna Summer. The album temporarily disappeared from streaming because of distribution companies’ reluctance to work with him.

Ye’s rapping on Vultures was far from repentant. “‘Crazy, bipolar, anti-Semite’ / And I’m still the king” went one refrain. In another line, he defended himself by using the same logic that concentration-camp guards could have used to refer to their sex slaves: “How I’m antisemitic? / I just fucked a Jewish bitch.” The music itself was grandiose, churning, and gothic—but like most of Ye’s work since the mid-2010s, it was also underwritten, poorly paced, and mostly forgettable. Yet “Carnival” did stand out, thanks to a sampled vocal of Italian soccer fans rowdily chanting the hook. In his verse, Ye riffed on his pariah status in the gasping tone of a street preacher: “Now I’m Ye-Kelly, bitch / now I’m Bill Cosby, bitch / Now I’m Puff Daddy rich / that’s Me Too me rich.”

For any song to reach No. 1 on the Hot 100 these days does not necessarily mean it is an era-defining, unescapable smash. The construction of the Billboard charts factors in streaming, which allows pluralities of fans to send a song up the charts by listening to it on repeat. (Remember, before streaming, the number of times you played a song privately didn’t influence its popularity.) Gunning for the No. 1 spot has thus become like a game of capture the flag for pop fandoms and even political projects. Ye posted repeatedly about the song’s chart performance, encouraging diehards to help push “Carnival” to No. 1. But, holding strong at No. 4 on this week’s Hot 100, the track is likely also catching on among a broad base of hip-hop fans.

The song’s appeal is partly musical: Its adrenalizing vocal loop sits atop a bone-crushing bass line recalling Sheck Wes’s “Mo Bamba,” the 2018 song that helped set the template for a recent strain of hip-hop that seeks to create punk-rock-style mosh pits. The song also features the rage rapper Playboi Carti, a young cult celebrity who hasn’t released a full album since 2020. Ye’s own verse is situated midway through the song, among those from three other emcees (Dolla, Carti, and Rich the Kid). He’s effectively taking an edgy, subcultural sound and executing it with blockbuster production—a classic pop-star move.

What’s more, Ye remains talented at linking his personal mood with a broader social climate. The mesmerizing “Carnival” music video depicts a tableau of men—some looking like skinheads, others like police troopers—brawling with one another. The imagery draws on soccer riots, but also induces thoughts of factional war, male anger, and the apocalypse. Whereas Ye’s lyrics compare him to various alleged monsters such as Cosby, the other featured rappers traffic in more standard-issue pop misogyny, depicting sex as an act of material and physical subjugation. All in all, “Carnival” really does crackle with a sense of menace, a feeling of macho alienation cohering into a mob.

“This number #1 is for … the people who won’t be manipulated by the system,” Ye wrote on Instagram. He’s right, if you consider the system to be the entrenched commercial institutions motivated to ice out Nazis. But in other ways, he has used the system available to him—the levers of streaming and social media—to win this hit. And the record industry, in which moral postures are informed by money-minded risk management, may well warm to him a bit now that he’s at No. 1. For example, last week, he played at a major festival, Los Angeles’s Rolling Loud—a low-effort performance in which he essentially did karaoke onstage.

To enjoy a song as catchy and powerful as “Carnival” is, of course, not to endorse any particular ideology; the song’s surging sound is an equally effective spur to lift weights, vent about work, or plan a coup. Nevertheless, the song’s popularity is being spun by Ye as vindication of his own righteousness, and will no doubt further energize the worst segments of his supporters—such as the ones who draped a banner over a highway that read Kanye was right about the Jews. Pop music ultimately succeeds or fails according to principles of pleasure, not politics, but the perception to the contrary holds its own danger.

Source: theatlantic.com